“Such is the condition of humanity, and so uncertain is men’s judgment, that they cannot determine even death itself.” - Pliny the Elder

In the 18th and 19th centuries, a specter haunted the minds of the living—it lingered in limbo, where darkness weighs heavy, and the air is thin.

If found in its confines, no course of action nor thrash of panic could save you. You were as good as dead.

How morbid it must be to realize the very reason you’re trapped in this nightmare at all is because everyone you know already believes you to be dead— entombed in a world where the line between life and the grave is weaker than your last gasp of breath.

Your fate echoes above the tolling of the church bells or the screams of the undead. You’ve just been buried alive.

I’m Kate Naglieri. Welcome to The Bygone Society Show.

Death is Uncertain - Proverb

Legal death was once a murky concept. It was not based on the certainties of modern medicine but on practices that often…faltered.

You have to remember, Traditional Western Medicine of the 18th century gave way to the tentative strides of Early Modern Medicine in the 19th century, but both were built on the bones of stolen bodies – thanks to the common practice of grave-robbing – as well as morally-questionable experimentation, and rudimentary practices.

Coupled with frequent epidemics like cholera, smallpox and influenza, and a thick sense of superstition, mortality stalked the populace like a silent and ever-present predator.

The fear of being buried alive gripped the collective consciousness, as science struggled to distinguish life versus its dark twin – where anyone, regardless of age or gender or standing, could be found in its cold resting place.

The Universal Terror of Premature Burial

Taphophobia, or the fear of being buried alive because of incorrectly being pronounced dead, was a common fear, even among the historically famous.

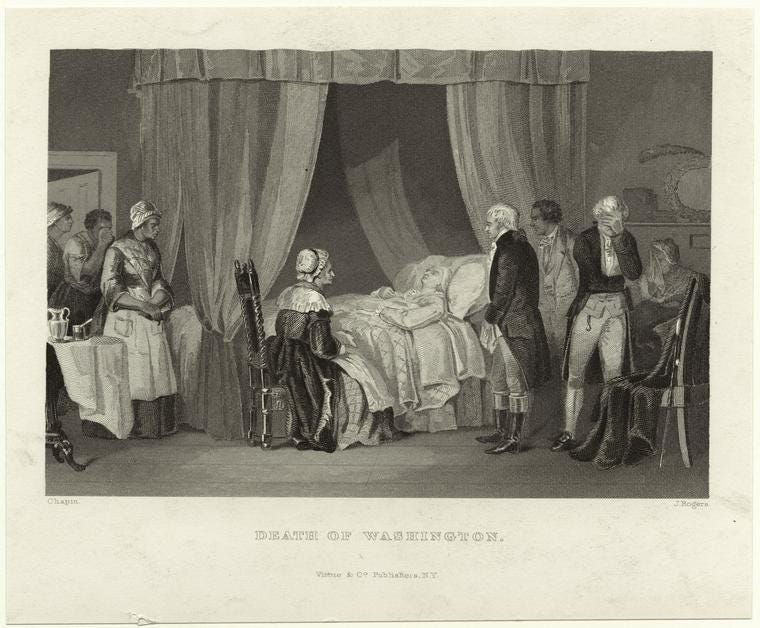

First President of the United States George Washington was so fearful of being prematurely buried that he instructed his secretary Tobias Lear while on his deathbed, saying: “Have me decently buried; and do not let my body be put into the Vault in less than three days after I am dead.”

Washington wasn’t alone in his fears. Edgar Allan Poe, the Master of Macabre, feared premature burial so much, he wrote the Gothic short story, The Premature Burial.

I love a no-frills title.

Here’s a passage that vividly illustrates Poe’s imagined experience of being buried alive:

“It may be asserted, without hesitation, that no event is so terribly well adapted to inspire the supremeness of bodily and of mental distress, as is burial before death. The unendurable oppression of the lungs -- the stifling fumes from the damp earth -- the clinging to the death garments -- the rigid embrace of the narrow house -- the blackness of the absolute Night -- the silence like a sea that overwhelms -- the unseen but palpable presence of the Conqueror Worm.”

Frequent references to premature burial in literary works embedded the concept deeply into societal consciousness, turning it into a naturalized element of Gothic culture and conversation.

For example, Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” features the Headless Horseman, a ghost of a Hessian soldier who was buried alive.

Or take the Tale of Enoch Crosby, a spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, who was captured and buried alive by the British. According to legend, he managed to escape his grave and continued to serve as a spy.

And then there’s the true story of Margorie McCall, a woman from Lurgan, Ireland. She fell ill with a fever and was declared dead in the late 17th century. She was buried swiftly to prevent the spread of disease, and was interred wearing a valuable ring that grave robbers set out to steal.

When the robbers attempted to remove the ring by cutting off Margorie’s finger, she awoke from her cataleptic state, terrifying the robbers and causing them to flee. Margorie then climbed out of her coffin and returned home, shocking her grieving husband and children. She lived for many years after, and even had another child.

Her final resting place famously reads, "Lived Once, Buried Twice."

The Great 'Dead' Watch: When Legends and Laws Intertwined

Stories and legends hold a great deal of power and are often used to shape new policies.

As the fear of premature burial came to a cultural crescendo, early activism emerged to prevent accidental, and sometimes careless, tragedies.

A mid-18th century thesis, written by Danish-born French anatomist Jacob Winslow and translated and augmented by French physician Jean-Jacques Bruhier, describes 181 cases of people presumed to be dead who rose from “their Shrowds, their Coffins, and even from their Graves.”

Bruhier and Winslow’s dissertation alerted the public, carrying the strong and odorous message that putrefaction was the only sure sign of death.

Which takes us, dear listener, inside the dim and somber walls of the deadhouse.

Designed to ensure bodies showed no signs of life, deadhouses were a type of waiting room that addressed the fear of premature burial by waiting and watching dead bodies for up to 72 hours as they decomposed.

These large rooms featured functional furniture, good ventilation, and sometimes alarm systems, allowing family members or hired personnel to keep vigil. The decor was often dark and muted, providing privacy and comfort for those observing the deceased.

Deadhouses could be found all over the world. Take, for instance, the Leichenhaus in Germany, also known as “asylums for doubtful life,” which surfaced between 1800 and the 1830s.

Travel due west to Paris or due east to Vienna and you would have found “waiting mortuaries.”

At one time, the Morgue de Paris, could accommodate up to 180 bodies visible through glass windows. What was intended to ensure death and assist family members in identifying lost loved ones, the Morgue de Paris soon became a popular morbid spectacle, attracting hordes of onlookers of all ages; men, women, the elderly, even children pressed their faces to the glass that separated them from the deceased laid out in various states of repose.

The morgue soon transformed into a grim and unsettling interrogation room, where confronting one's victims unfolded like a chilling scene from your favorite crime show. However, in the mid-19th century, this drama could be witnessed live.

Authorities frequently escorted suspected murderers to the crowded morgue to stand face-to-face with their victims, hoping the sight would elicit confessions. By 1888, they had electric lights installed in the morgue to heighten the impact on perpetrators facing their handiwork. The intense glow intensified these harrowing confrontations, compelling the guilty to reckon with their deadly deeds.

Saved by the Bell: And Other Methods to Prevent Premature Burial

In contrast to the dramatic displays at the morgue, Victorian doctors approached their work with a methodical and increasingly scientific approach. Equipped with sparse but essential medical instruments, these physicians relied on observations and tests to determine the cause and time of death.

Victorian doctors employed instruments like the stethoscope, thermometer, and ophthalmoscope to gather clinical evidence. The stethoscope enabled them to listen for vital signs, the thermometer to measure body temperature, and the ophthalmoscope to examine the retina for telltale signs of decomposition. For more detailed investigations, a hypodermic syringe was used to test for responses such as inflammation to ammonia injections, while a magnesium lamp aided in detecting signs of circulation in the extremities.

But no one test or sign was as reliable as carnal decomposition.

That’s why, in 1896, Dr. William Tebb partnered with Walter Hadwen to establish the London Association for the Prevention of Premature Burial.

The organization aimed to raise awareness, advocate for safety measures, educate the public and medical professionals, and sometimes lobby for legislative reform to prevent incidents of premature burial.

The association garnered public sympathy and backing for its campaign to prevent incorrect death diagnoses and premature burial, but it drew criticism from the medical community, who deemed their outreach sensational and unwarranted.

Nevertheless, the emergence of innovative solutions and medical patents soon followed—whether motivated by opportunistic profit-seeking from the moral panic of everyday citizens or driven by genuine humanitarian concerns for their wellbeing, is a matter open to interpretation.

As for me, I’d say it was a bit of both. As is the case, usually.

Here’s a short list of practical and bizarre methods and technologies invented to make sure the dead were in fact, dead:

First up we have safety coffins equipped with various mechanisms to signal to those above ground that someone was buried alive. The most popular method was the inclusion of a bell hung above ground by one end of a string, with the other end tied to the finger or hand of the deceased six feet below. If the person happened to stir, it would ring the bell—truly a case of being "saved by the bell."

I can see it now: A morbid prototype of the teen sitcom first released in 1989, where life's real cliffhangers have a much graver consequence.

Then there was the scientific exploration of Galvanism Death Tests.

Named after Italian physicist Luigi Galvani, Galvanism involved the application of electrical currents to animal tissues, resulting in muscle contractions that could mimic signs of life.

Galvani's experiments sparked discussions about the potential for using electricity to revive the dead—a concept famously explored in Mary Shelley's novel, Frankenstein.

Much like her well-known literary pariah, dead animals and cadavers were hooked up to electrodes applied at the temples or chest, where an electric current would pass through. The hope was to observe muscle contractions or movement, further exploring the edge of life and death.

Other means of revival involved doctors vigorously rubbing the dead with wool, or blowing tobacco smoke up their rectum with bellows, or forcibly cranking their tongue, all in an attempt to stir them awake.

Still, others would hold a finger over a flame or amputate a toe in the hopes that the pain would jolt them back to life.

A Final Respite: Midnight Mary’s Warning

As for the unfortunate souls already buried, with no safety precautions in place, their fate was sealed.

Or was it? In our final account of premature burial, it wasn’t scientific curiosity but a dream, or rather, a nightmare, that almost prevented the death of our last victim, Mary E. Hart.

Little is known about Mary Hart, other than when and where she was born: December 16, 1824 in New Haven, Connecticut and when and where she died: At midnight on October 15, 1872 in her place of birth at age 47.

How she died is less concrete.

Legend has it, a few months before her 48th birthday, Mary dropped to the floor, perhaps due to a stroke or some other illness.

Presuming her to be dead, Mary’s husband and extended family buried her at Evergreen Cemetery the very next day.

One night soon after, Mary’s aunt – though some retellings say it was Mary’s sister – woke from a terrible nightmare. In it, Mary was not dead, but had, in fact, been buried alive.

Believing the dream to be real, her aunt (or sister) convinces the rest of the family to exhume Mary’s body from her grave.

When they pry open her casket, they’re shocked and horrified to find her fingernails bloodied from frantically scratching the top of the coffin and a look of sheer fear contorted across her face.

I recently visited Mary’s pink granite gravestone at Evergreen Cemetery, where her epitaph reads:

« At high noon just from, and about to renew her daily work, in her full strength of body and mind, Mary E. Hart, having fallen prostrate remained unconscious, until she died at midnight October 15, 1872. »

Along the top of the plaque, it states: « The people shall be troubled at midnight and pass away. »

The passage from the book of Job in the Old Testament was likely included as a sign of Mary’s fate to have passed, or seemingly passed, at the stroke of midnight.

But over time, it’s taken on a foreboding warning for residents and visitors of New Haven: All those who dare reside by Mary’s grave past midnight will soon follow her to the grave.

New Haven is home to several colleges and universities, including Yale and Southern Connecticut State. Campus rumors tell the frightening stories of young students who dare visit her grave at midnight, only to be found bound to it with a look of terror across their faces.

And children know all-to-well that if they’re to misbehave, Midnight Mary might just come for them.

Stories like these have been passed down through generations, not just to frighten, but to teach and protect.

They serve as cautionary tales, warning the young and adventurous of the dangers that may lurk when curiosity leads them astray. As for myself, I can’t help but be reminded of that thin though ever-present veil between life and death, and the respect that must be paid to both.

As Edgar Allan Poe so thoughtfully considered:

“The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?”

Thank you for joining The Bygone Society Show. If you’re already a mega member and fan, consider sharing your favorite episode with friends and family who also enjoy taking a walk down history’s eerie lane.

xx

Sources:

‘Midnight Mary’ continues to haunt Evergreen Cemetery in New Haven (nhregister.com)

The New Haven Green: There's A New Haven Burial Ground Hiding Under This Connecticut Green (onlyinyourstate.com)

Midnight Mary, New Haven – Damned Connecticut (damnedct.com)

The Fear of Being Buried Alive (and How to Prevent It) - JSTOR Daily

Buried Alive – The National Museum of Funeral History (nmfh.org)

When Fears of Premature Burial Stalked the Land - New England Historical Society

New Haven, CT - Midnight Mary's Grave (roadsideamerica.com)

The lady lived once, but was buried twice (bbc.com)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/345608

(Grave Doubts: Victorian Medicine, Moral Panic, and the Signs of Death

Author(s): George K. Behlmer

Source: Journal of British Studies , Vol. 42, No. 2 (April 2003), pp. 206-235)

Share this post